An analysis of all Facebook posts from U.S. law enforcement agencies revealed widespread overreporting of Black suspects.

Feb 27, 2023 Nikki Goth Itoi

Over the last decade, social media channels have become a go-to resource for the public to follow local news, including crime reports. On Facebook, more than 14,000 U.S. law enforcement agencies communicate directly with their communities. Facebook itself has played an active role in helping them build agency pages with its guide for police departments , a PDF of best practices for “creating a dialogue with the community.”

But do these pages present an accurate picture of the relationship between crime and race, or do they reinforce harmful stereotypes? A team of legal and policing scholars applied natural language processing to data extracted from the Meta tracking website CrowdTangle to find out.

By studying the language used in social media posts, they have put the spotlight on a troubling trend: Police agencies on Facebook overreport on Black suspects in all violent crime categories. Looking at all agency posts between 2010 and 2019, Black suspects were described in 32 percent of race-crime posts but represented just 20 percent of arrestees.

“The arm of the state that’s principally responsible for controlling crime also shapes public views about character and incidence,” says Stanford Law School Associate Professor Julian Nyarko . “What we’re seeing is a worrisome pattern of agencies overreporting crimes that involve a Black person.”

Read the full study, Police agencies on Facebook overreport on Black suspects

Prior research has examined whether overreporting is happening in traditional media, with mixed findings. But today’s social platforms represent a new communication channel between the public and law enforcement agencies. “We wanted to understand how Facebook changes the existing patterns,” Nyarko says.

Nyarko collaborated with Ben K. Grunwald , professor of law at Duke University, and John Rappaport , professor of law at the University of Chicago, to design a study that could measure overreporting — a ratio between crime news that involve a racial description and actual crime stats — and overexposure — a measure that compares how many times viewers encounter posts about crime news relative to the actual, local incidence rates.

The researchers used two main sources to build their data set for the study: posts extracted from the CrowdTangle website, which tracks interactions on public content from Facebook pages and groups, and official crime statistics from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program.

A keyword search of CrowdTangle produced 12,071 police agency pages on Facebook, with another 1,919 pages found in a manual search. From these agency pages, the team identified 11 million posts published during the 2010-2019 time span. Since police agency posts can cover a wide range of topics, from local events to emergency info to lighter, entertaining content, the researchers needed a way to find crime-related posts that included a description of race. For this, they turned to machine learning.

From the master set of posts, Nyarko and team first applied keywords commonly used to indicate race (Africa, Arab, Asian, biracial, Black, Brown, Caucasian, Hispanic, Latin, Mexic, skinned, White). To confirm whether the keywords were actually used as race descriptions in the specific post, they employed an algorithm from a previous study developed to mask race descriptions in police reports. From the resulting posts with race descriptions, they selected a random sample of 990 posts to label by hand. With their training data at the ready, they took three different approaches to classifying the larger set of posts:

Combining these approaches yielded an initial set of 100,000 posts that reported on the race of individuals arrested or suspected of crime. Since the FBI’s OCR (Office for Civil Rights) database contains more complete arrest data for the category called Part 1 offenses (murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, automobile theft, and theft), the team decided to further refine their focus to 70,000 posts that referred to these severe crime categories.

With each method, Nyarko says they trained the models on their hand-labeled data 10 times, holding back a different 10 percent of the data set, which was later used to test the model’s performance.

As they prepared to analyze the results, the researchers considered two key questions:

To explore the question of overreporting, researchers calculated agency-level scores from the data set and found on average that Black suspects were described in 32 percent of race-crime posts but represented just 20 percent of arrests. “ Even though an agency might have good motives for what it posts, this pattern creates a skewed view of race and crime,” Nyarko explains. “Sometimes you’re not targeting minorities; but what you publish can have unintended consequences.”

The degree of overreporting by agencies on Facebook was concerning, but this measure didn’t factor in the way that posts get amplified through social media channels. For example, Nyarko notes, people often see crime news not only from their local police department but also from neighboring jurisdictions. And multiple agencies might decide to run the same story, giving it even more exposure to the audience. Moreover, if the volume of posts on an agency’s page is low, the impact of a single arrest post could be outsized. Finally, Facebook users often share crime posts with their followers, which increases the degree of overexposure.

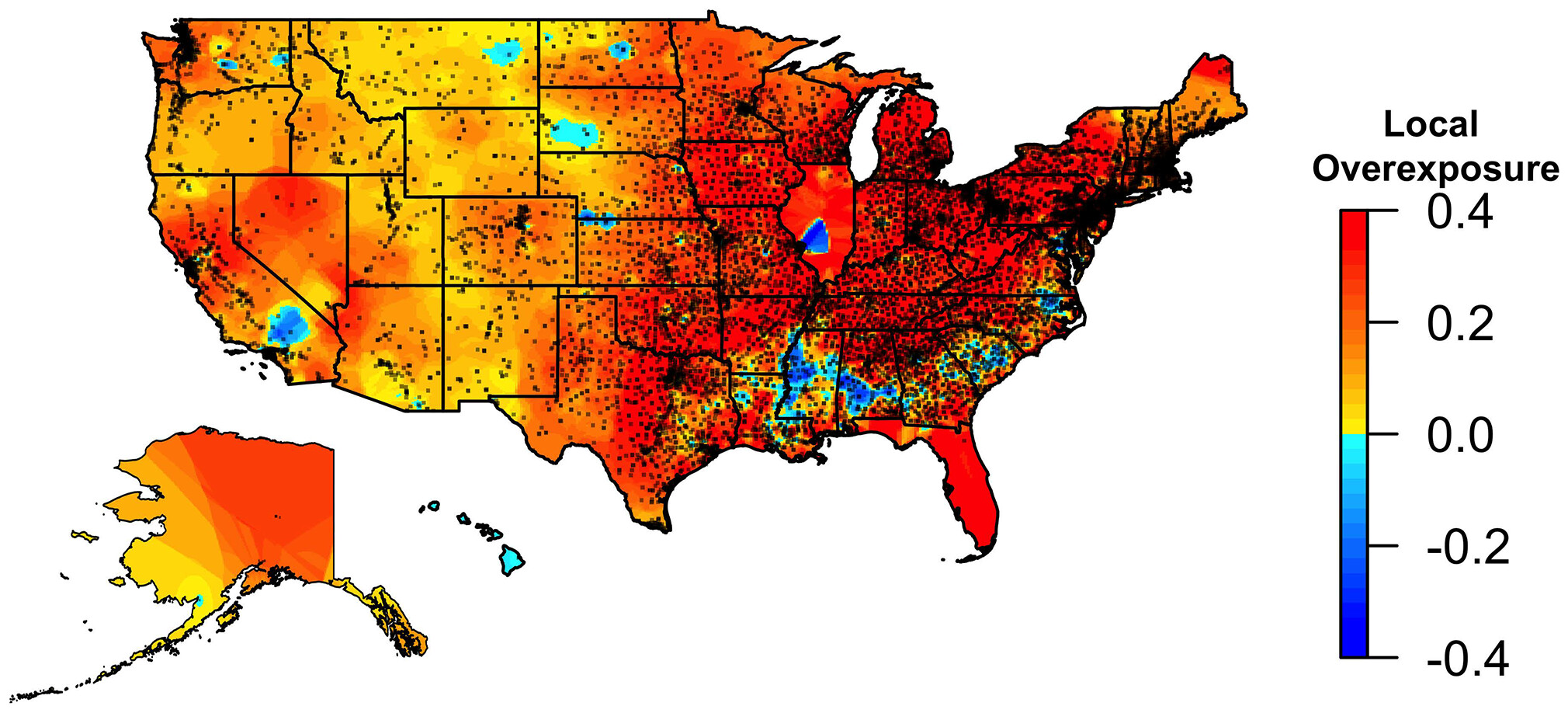

Ultimately, the research revealed that Facebook audiences were exposed to race-crime posts that overrepresent Black suspects by 25 percent relative to local arrest rates. Given that the average arrest rates for Black arrests was 18 percent, the relative overexposure was 138 percent. By using Google Maps and the OCR database to locate agencies in the data set, the team was able to map estimated overexposure levels across the U.S. Only Hawaii and the Black Belt in the South defied the overall trend.

Heat map of overexposure in the United States.

“We were surprised to find such a widespread effect,” Nyarko says. “We went into the study thinking the results would be more heterogeneous, but when you look at the heatmap, overexposure is everywhere.” Perhaps more striking still, researchers found that the level of overexposure was even more pronounced in Republican counties, using voting record data in presidential elections during the 2010-2019 timespan.

Many assumptions had to be made throughout each step of the study, and the team details each decision in the paper. A couple of limitations are worth noting: For the measure of overexposure, they chose a fixed geographic radius of 300 miles from any given agency. Accordingly, the analysis assumed that the likelihood of someone seeing a post from an agency at a given physical distance is consistent across the country. In reality, the probability could vary, depending on whether the agency’s location is rural, suburban, or urban. A related limitation is that the researchers could not directly observe which Facebook users viewed which police agency posts.

According to the results of this study, crime news as presented and experienced on Facebook does not accurately reflect crime patterns in the local community. Now the question is, what to do with this insight? For a next step, Nyarko says the team would like to explore other social channels, such as Next Door, and to dig more deeply into the correlation of overreporting and overexposure with political ideologies.

He also hopes this research will spark a dialogue about the practice of including race descriptions in crime posts. Except in the rare case of enlisting community support to apprehend a suspect at large for a particularly severe crime, it seems unnecessary and more likely to be harmful, he says: “Any perceived benefit must be weighed against the real costs for the Black community and for society at large.”

Stanford HAI’s mission is to advance AI research, education, policy and practice to improve the human condition. Learn more